The Chestnut Group, a brief history

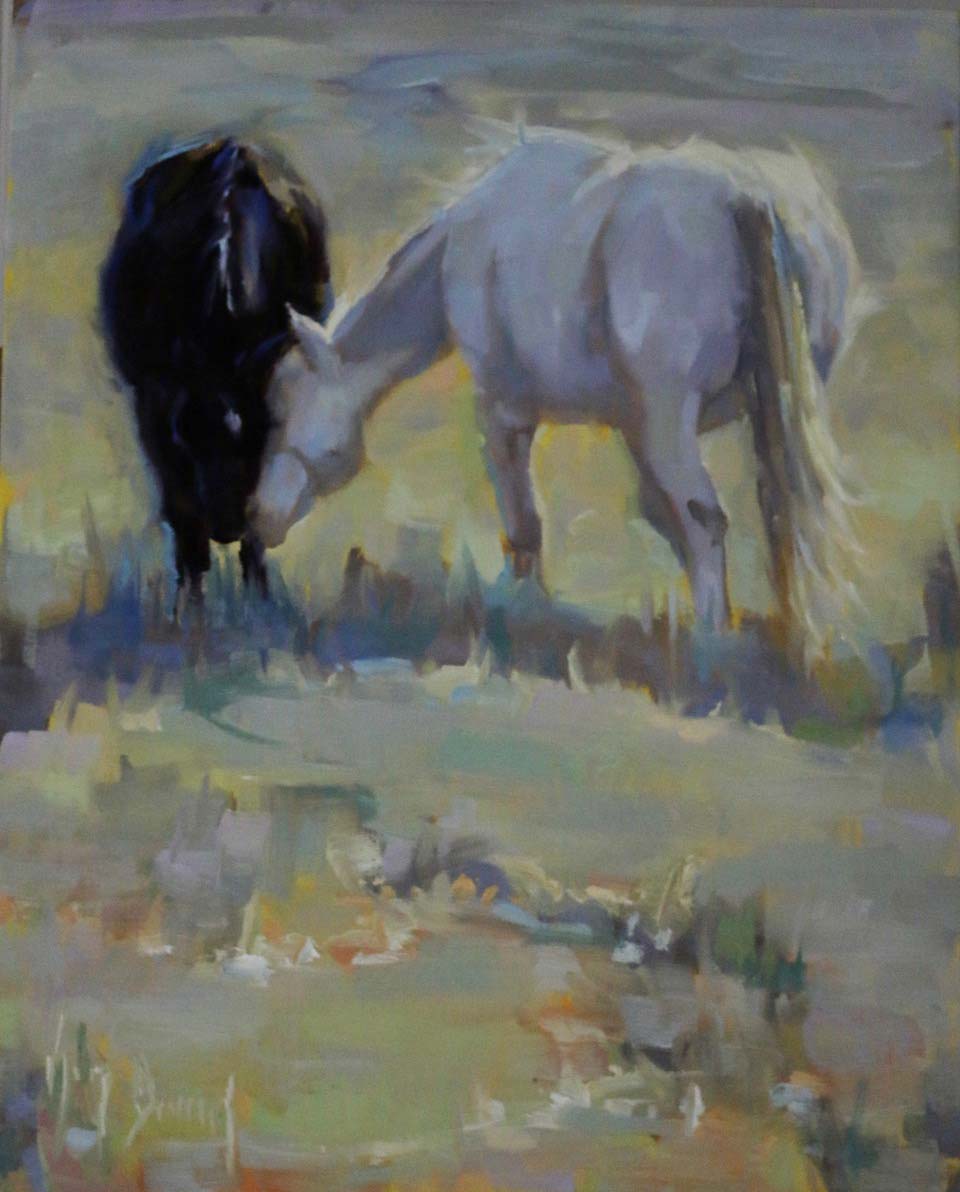

On a chilled November 10, 2001, about a dozen outdoor painters gathered together for a photograph. The photographer was the husband of Connie Ericson, the first president of The Chestnut Group. The day was clear with blue sky above the bare trees. The artists were arranged in a pleasing composition huddling close for warmth. We had just finished working in the pristine, wooded hollow beside Kelley Creek at the invitation of Paul and Margaret Sloan, benevolent guardians and owners of Kelley Creek Farm. It was on this day, in a place so rich in biodiversity, that we began the work of our mission. To come together and be a part of the effort to save places so beautiful or old or fragile that the loss of them would be tragic to us as artists, to our children and to future generations.

Kelley Creek was a perfect place to start our efforts. It had been identified by The Nature Conservancy as the one of the most precious of the diminishing, unique, ecological fragments in Middle Tennessee. Kelley Creek is unceasingly spring fed allowing rare creatures to flourish. It was a place of exquisite stillness that day, and all those who had the privilege of attending that first excursion were changed by days end. This was our first painting excursion, trips we would continue to take together. Diane May later tagged them “Wet Paint’ parties.

The idea for this band of painters came from an article published in American Artist magazine that drew my immediate attention earlier that year. It still astounds me how much this concept resonated with so many painters, more than I could have imagined. Originally the idea was to form a small group of 10 to 12 painters, similar to The Oak Group, which was described in the article. These California artists came together as a result of a painting excursion to a favorite coastal spot. When they learned of its planned demise, like so many properties in the recent past, they were angered. As I remember, they took their paintings from the excursion, sold them and gave the funds to a group fighting the development of the place they treasured. They continued their efforts and raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight other such developments. They are apparently still active today.

It was the efforts of a handful of inspired folks, doing what they loved and did best, but working for a greater good that moved me. It was just what I had been searching for; a way to paint and help with something I really believed in doing. Since attending Vanderbilt Divinity School, I found little that was important in life unless it connected to something with a greater mission. As I discovered, I wasn’t the only one who searched for something like this in their lives.

I contacted Connie Ericson, an established artist and teacher. I had met her as the instructor in my first outdoor landscape painting class a year earlier. Formerly in nuclear medicine, she had left Vanderbilt to pursue a full time career as a portrait artist. The idea I presented appealed to her and she immediately contacted a number of other established artists she thought might be interested. I was struggling with making a move from student to professional artist at the time, and brought mostly enthusiasm to the group. My only other contribution was some business and organizational skills, a result of a previous life as a local banker.

Connie also was the source of the name The Chestnut Group and “plein air painters for the land”. We both were familiar with the tragic story of the decimated forests of chestnut trees. The American chestnut was the most prevalent tree in the Southeastern United States until the early part of the last century. A virus swept through the forests, causing trees to become ill and eventually to die. In reaction to the virus, people began harvesting the trees, believing they were to lose them due to the blight. The conventional wisdom of the time was to at least save the wood products from an inevitable destruction. Unknowingly, this further crippled the chestnut population, and nearly wiped out the entire native species. Efforts continue today to bring back this valuable tree; revered for its tough wood and also as an abundant food source. The chestnuts themselves are enjoyed by humans and animals alike. It was the right name and has served us well.

As in so many stories, there were moments of grace or serendipity that supported our cause. I had always wanted to somehow become involved with the efforts of The Nature Conservancy. Having had a decade long career in finance and banking, I respected the pragmatic approach this conservation group took. They have executed a systematic plan which has saved countless fragile places all over our planet. I decided that somehow I would make them our first beneficiary.

Now, why I thought they might agree to let a bunch of artists “help” them, to this day I am unsure. It seems obviously an insane idea looking back. Armed only with a copy of my magazine article I called TNC. I was granted a meeting with a young staffer, whose job it is clear to me now was to filter out well meaning nut cases, like myself. Her name was Amy Garner (now Jerome) and she was housed at the Tennessee chapter office located in the lovely old St. Bernard’s convent. We have laughed often about why she ever agreed to the wild suggestion. Whenever I try to discover what it was that moved her in our favor, she is politely vague.

This was the first of many similar moments. It seems there are times when the purity of the artistic process touches others. Time and again people are moved by the mission to paint and then to preserve the land that inspires us. Painting outside changes us, the paintings move the viewer, funds are raised or at the very least, a piece of a place is saved on canvas. A moment in time, recorded in a deeply personally way not to be forgotten. Kinda sappy, but true none the less.

These accidental connections have earned me the reputation of being the “Forrest Gump” of plein air painting. The Chestnut Group has been fortunate enought to stumbled into more opportunities than we have been able to give the attention they deserve.

The Nature Conservancy directed us to the Sloans of Kelley Creek, who in turn advocated local landscape art and its connection to conservation. They connected us with the Land Trust for Tennessee and most importantly treated our efforts with a level of respect which drew the interest of some of the best landscape painters in the country and patrons to enjoy our efforts.

Matt Smith, recently noted in Art of the West as one of the next generation of Master Painters, and a member of PAPA (Plein Air Painters of American, the oldest group of its kind in the country) was our first guest to Tennessee. He taught a workshop, participated in our first paintout, and began the tradition of guest artists donating a work of art to our fundraising efforts.

The first event was held on a drop dead gorgeous spring day on the adjoining properties of Kelley Creek Farm and the land owned by Kim and Charles Crew. Artists were spread over 3,000 acres of fields, streams, and woods. It lasted all afternoon and ended in an exhibit and sale benefiting TNC and The Land Trust for Tennessee. Jeanie Nelson, executive director for TLTT credited the event with aiding in the Crew’s decision to place their property in a land trust. I would like to believe her on this.

The Chestnut Group today is not what I envisioned as I clung to the ragged magazine that fall of 2001 and showed to anyone who seemed even slightly interested. I hoped that a few kindred spirits out there would want to paint outdoors and help keep as many trees around to hug as I did. Little did we know just how many “nuts” as we eventually called ourselves, were waiting to be cracked. A group that fall including Joan Walker, our first secretary (who coined our motto “We’re Out There”), Kate Donnelly, our first vice president, and Claudia Williams, (still our website/ email guru) and several others were some of the first and most enthusiastic to join in the fracas.

The Chestnut Group is now more than 6 years old. Over this time, we with our partners have raised somewhere up or down around $100,000 for a number of environmental/historic preservation groups. We have encouraged numerous aspiring artists to go outside and be a part of the natural world in a quiet intimate way. We have challenged the most experienced landscape painters in the region to show us how to do this better, more skillfully. We have taught each other to capture Tennessee more authentically, as instructors, peers or students.

To me though, the most important thing TCG has done is to create a way for us individually, to be more than what we were. We are artists. Before TCG, I heard it said that “no one buys Tennessee landscapes” and “you can’t paint Radnor Lake, the light moves too fast.” But the combined efforts of TCG artists saw more. We can be who we are and be better also. When we are serving something greater than ourselves, when we donate our time or artwork, we are changed for the better. We have fallen in love with our beautiful state, the Tennessee landscape and our love shows in our work. We have on occasion made other people stop and look at what we are painting. And those watching us have maybe pondered what was so intriguing about that spot. And that is how we make a small difference. Might be just inside us, or it might be more.

It has been an honor to watch this organization thrive. It seems so simple now. It makes sense.